Navigate to Sections

Panjakent (Russian: Пенджикент) is an ancient city in Tajikistan’s Sughd province, with origins in pre-Islamic Sogdian society (circa 6th century BCE – 11th century CE), situated on the Zeravshan River in the Zeravshan valley (Zeravshan is a Persian word meaning “spreader of gold”). Panjakent comes from Persian—“panj” meaning five and “kant/kent” meaning settlements, so it translates to “five settlements.”

The city was an old trading center of the Sogdian empire because of its proximity to Samarkand and Bukhara, well-known cities of the time.It is also the birthplace of the renowned Tajik poet and philosopher Rudaki, who is considered the father of Persian poetry. His statue can be seen in Dushanbe parks, and there is a history museum named after Rudaki in Panjakent.

The total population of present-day Panjakent was 52,500 in 2020. The city is easily accessible from the capital Dushanbe or the neighbouring country, Uzbekistan, which is a popular tourist attraction, like Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva. The city and nearby Zeravshan region are known for their breathtaking natural scenery, including the Fann Mountains, alpine lakes, and ancient archaeological sites.

Access to Panjakent and Border Crossing

Travel from Khujand or Dushanbe:

- Panjakent is accessible via a 5-hour journey from either Khujand or Dushanbe, but both routes require crossing high mountain passes.

- From Khujand, travelers must cross the Shakristan Pass (3,380 m). This route from Khujand can become extremely cold and, during winter, sometimes impassable, cutting off access due to snow and harsh weather.

- From Dushanbe, the route is about 230 km, passing through the Varzob Gorge and over the Anzob Pass (3,370 m).

By Air:

- Panjakent has a small local airport with occasional flights to Dushanbe. There is no fixed schedule; flights operate only when mountain passes are closed and enough passengers are available.

From Uzbekistan (Samarkand Route):

- Most visitors arrive from Samarkand, located just across the Tajik border.

- You must have a valid Tajik visa, and if returning the same way, a double or multi-entry Uzbek visa (if required by nationality).

- There is no public transport across the border, and travelers typically change taxis at the border unless the journey is prearranged through an Uzbek tour agency.

Border Crossing (as of October 2025):

- Crossing the border, particularly from Uzbekistan to Panjakent, appears smooth and hassle-free.

- Officials simply check passports, stamp them, take a photo, and allow travelers to pass. No questions, no luggage searches, and no reported complications.

We rented a taxi to travel to Panjakent from Khujand to spend two days exploring the area. Afterward, we continued our journey to Samarkand, crossing the road border from Panjakent.

During our two-day stay in Panjakent, we visited the Rudaki Museum (Republican History and Regional Studies Museum), the Olim Dodhko Mosque and Madrasa, Kainar Ato Spring, the ruins of ancient Panjakent, and the Sarazm settlement.

The Rudaki Museum (Republican History and Regional Studies Museum)

The Rudaki Museum in Panjakent is a well-restored local history museum that should not be missed. It is named after the 10th-century famous poet Abu Abdullo Rudaki who is also known as “Adam of poets” and one section of the museum is dedicated to the poet.

You will also find some fascinating artifacts from ancient Panjakent, including frescoes depicting banquets, battles, and everyday life, as well as statues of Zoroastrian deities and a wooden figure of a dancing woman. The museum also exhibits items from the nearby Sarzam, a Neolithic-era archaeological site a few miles further west, including the famous “Princess of Sarazm” (a must-see) at the museum. (You will find more information about the princess later in teh archaelogical section of sarzam settlement of the blog)

Additionally, traditional Tajik crafts and clothing, Soviet-era history, national independence, and local wildlife exhibited in the museum provide a comprehensive insight into the region’s ancient history and culture.

Olim Dodhko Mosque and Madrassah

This complex, located in the eastern part of Panjakent, includes an 18th–19th-century Friday Mosque that can hold up to 1,500 worshippers. The site comprises a Friday mosque, madrasa, and mausoleum, situated in a green area just off the main road. The complex is somewhat neglected, but you can get an idea of the historical architecture in Panjakent. A local caretaker opens the mosque upon request, but we did not have the chance to see inside as it was closed for renovation. This 18th-century mosque and madrasa near the central bazaar offers a glimpse into the era of the ancient trade route, with a market, mosque, and madrasa typical of Central Asian cities along the trade route.

Friday mosques in Central Asia hold special significance because Friday is the holiest day in Islam, when Muslims gather for the required communal prayer called Jummah. A “Friday mosque,” or Masjid-i Jami, is the main mosque in a city where this prayer is held. These mosques have historically been more than places of worship; they have also served as centers of community life, hosting social and political gatherings. Since they needed to accommodate large crowds, Friday mosques were usually the biggest and most important religious buildings in the city.

Historically, since people gathered at the mosque for Friday prayer, many merchants took advantage of the crowds by selling their goods nearby. Over time, these gatherings developed into markets around the mosque. To support traders, caravanserais were built to provide lodging and storage, and many trading centers emerged along trade routes, with the mosque at the heart of community and commerce.

Panjakent Bazaar

Checking the local bazaar was one of our to-do things in any Central Asian city we visited, so we also went to the Panjakent Bazaar, which is located right across from the mosque complex. This is an old, covered market, dating back to medieval times, running along the routes once used by caravans. It still has the same vibrant atmosphere, women selling fruits and vegetables, samsa, and nan. Since the Panjakent Bazaar is the town’s primary market and a lively hub, you will find many locals buying and selling fresh produce, nuts, spices, bread, and dairy products, as well as household goods, clothing, and traditional crafts.

Kainar Ato Spring

Kainar Ato Spring, meaning “father Spring” or also “gushing father” in Turkic language, is a natural spring near the Zeravshan River that supplies most of Panjakent’s water.

According to legend, it was created when Ali, a descendant of Mohammed, visited the area and prayed to drive away serpents, which vanished and formed the spring. The site is famous both for its legend and its essential role in providing water for the city.

The City Vibe, Availability of Coffee and Draft Beer

As of November 2025, Panjakent is not a very touristy town. Its vibe is different from Dushanbe’s, and it is a relatively more conservative, laid-back place, but the people are humble and friendly. It is pretty common in Panjakent to come across kids who say “hello” when they find out you are a tourist.

There was only one spot, Coffee Bora Bora, where we could get coffee and salad. There aren’t many bars or pubs, and many local restaurants or chaykhana (teahouse) only serve bottled beer. Maybe some big hotels serve beer, but we stayed in an Airbnb and preferred local bars and restaurants, so finding both coffee and beer was a bit harder. However, we managed to find a liquor store to buy some wine.

Day Trip to Ancient Panjakent Settlement Remains (5th–8th Century)

The next day, we hired a taxi again to visit the ruins of Ancient Panjakent and Sarazm. You can comfortably visit both in one day, as we did. We started our trip at 10 a.m. and were back by 6 p.m.

Ancient Panjakent is located just outside the modern city of Panjakent. These ancient ruins belong to a major Sogdian city that flourished from the 5th to the 8th centuries. It has been called the “Pompeii of Central Asia” because of the well-preserved frescoes excavated there, many of which are now exhibited in the local museum.

Since 1947, excavations by the Russian Hermitage Museum have uncovered a vast array of artifacts at Ancient Panjakent. These include numerous frescoes, murals painted directly on the city walls, and a variety of objects such as ceramics, metalware, jewelry, coins, musical instruments, backgammon boards, and dice.

Archaeologists estimate that Panjakent was founded in the 5th century. By the 6th century, it had expanded east and south, eventually being surrounded by a defensive wall. The walled inner city, known as the Shahristan, covered approximately 13.5 hectares and was divided into urban and suburban sections. Tragically, this inner wall was destroyed in the 8th century by Arab invaders.

The Temple Complex in the Shahristan

The Shahristan contains two similarly constructed temples, both dating back to the 5th century. Each temple was oriented east-west and featured two courtyards. The eastern courtyard provided access from the street, while the western one held a platform where the main temple structure stood. Entry was through a columned portico that led up a very narrow ramp to the main building platform. The main hall itself was surrounded by a gallery on three sides, and a door on the far side led to a rectangular cellar.

Although the main statues from the temples have been lost, a special building for the holy fire was constructed south of the temple complex in the late 5th or early 6th century, and the northern part of the complex, which was dedicated to water, still exists today.

Besides temples, there were eight main streets, ten lanes, shops, workshops, markets, and multi-room houses that had two or even three stories.

Residential and Other Architectural Findings

Archaeologists found a clear distinction between the royal and common residences. The homes of wealthy citizens in Ancient Panjakent were characterized by large, high-ceilinged main halls decorated with painted wooden carvings and sculptures. These halls ranged in size from 30 to 250 square meters, supported by four central columns.

Surprisingly, the palace of the ruler, Devashtich, was quite similar to these noble homes. Although it was slightly larger, the shared two-hall layout (one square and one rectangular), mirroring that of other nobles, suggests that his authority was perhaps not absolute among the powerful city nobles of the Shahristan.

It was also discovered that every family maintained a home altar dedicated to a protector deity, usually from the Zoroastrian pantheon. Citizens practiced idol worship; the image of the protector deity was molded from clay or possibly terracotta. For home worship, a large vase was placed near the entrance to the main hall, and a portrait of the deity, likely a family ancestor, was positioned nearby on a small column.

Ancient Panjakent Wall Paintings and Cultural Reflections

Over the past few years, extensive excavations at Ancient Panjakent have uncovered paintings on more than 50 building walls, unearthing a wealth of both large- and small-scale paintings that offer deep insights into the Sogdian civilization, daily life, and beliefs.

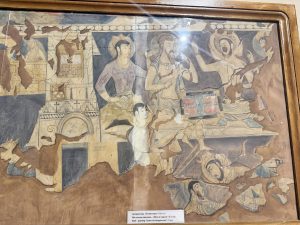

Several scenes illustrate stories from Firdausi’s Shahnameh (written by the Persian poet and writer Firdausi, 935–1020), featuring heroes like Rustam, Rakhsh, Suhrob, and Siyavush. The large-scale paintings across three walls of one shrine were composed of several independent and precisely themed scenes. Some of the frescoes covered nearly half of the wall surface. The most important depicts the hunt for seven “creatures” with zoomorphic designs, which were not purely secular but carried a sacred meaning. The paintings also depict specific contemporary historical events, such as the Arabs signing a peace agreement during the siege of Samarkand in 712.

Panjakent’s inhabitants clearly adorned their homes with gorgeous wall paintings. Among the most interesting are frescoes depicting musicians, dancers, hunters, warriors, feasts, wine drinking, wild boar fighting, and Hindu deities such as Shiva.

It is noteworthy that these paintings still survive after 1,300 years in the form of wall fragments, and they mostly used glutinous paints made with egg whites and mineral dyes, while rarely using plant dyes.

Wood carving was another prominent feature in Ancient Panjakent. All of the city’s largest buildings, including the main halls and porticos, were richly embellished with this decoration. During the conquest of Panjakent by the Arabs in 722, the palace in the citadel, one of the temples, and many houses belonging to the city’s nobles were tragically burned and destroyed. Many of these charred carvings are now displayed in the museum; the most prominent is the famous sculpture of a dancing girl. Thanks to the fire that preserved those carved wood pieces that were destined to decay over time.

Panjakent’s Strategic Importance

The Sogdians, while politically fragmented into small city-states like Panjakent, were one of the most culturally influential groups of their time due to their unparalleled role as commercial intermediaries. As master merchants and travelers, they dominated trade along the Silk Road between the 4th and 9th centuries, establishing extensive diaspora communities from their homeland (modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) to China. Their language became the lingua franca of trade routes, facilitating the flow of not just silk but also goods, art, and the major world religions—Buddhism, Manichaeism, and Zoroastrianism —across Eurasia.

Resistance and Decline

Panjakent’s ruler, Divashtich, fiercely resisted the Arab expansion into the region. This conflict culminated in a decisive battle at the castle on Mount Mug, where Divashtich was eventually captured and executed by the Arabs in 722. The Arab conquest ultimately led to significant destruction and the city’s eventual decline, with life largely ceasing in the 9th century. Although some activity continued until the 11th–12th centuries, the city was eventually completely abandoned.

The Present Ruins for Visitors: What to Expect at Ancient Panjakent

The ruins of Ancient Panjakent are a large archaeological site located on a hilltop, overlooking the modern town and the Zarafshan Valley. Because the buildings were constructed with raw, sun-baked mud and clay bricks that eroded over time leaving mounds and low foundations. Also, according to archaeological best practices, the site is usually covered back up (a process called backfilling) after study to protect it from decay, vandalism, and for future research, with only a few spots left uncovered for visitors’ interest and understanding. So, visitors have to rely on their imagination to visualize the original city. However, an on-site museum is available, displaying excavated artifacts such as pottery and ossuaries, along with photos or replicas of the famous wall paintings, which help provide the historical context and significance of the excavated areas, aiding in visualizing the city’s past development. Visitors should wear appropriate clothing and shoes and bring water, as the site is large, muddy, and requires walking and hill climbing to see the panoramic views of the surrounding city, river, and mountains. To make the most of the visit, it can be combined with other local sights. Lastly, a modest entry fee is charged for access.

Note: When we visited, the site looked abandoned, with kids and mules running around and over it.

Sarzam Settlement Overview

After visiting ancient Panjakent, we headed towards Sarzam, an ancient archaeological site. When we visited in October 2025, the site was well-maintained with marked covered excavation areas, and there was a walkable path to different sites. However, there were not many tourists.

Note: The settlement has a few excavated sections open to tourists, so they can get an idea of the architecture, layout, and materials used at that time. Archaeologists excavate and then cover them to protect them from further decay. You will see mud mounds, but the excavation history and relics are in the museum. Some people think the site is overrated, but we believe it was a great day trip that offered a lot of history about the region that once thrived along the ancient trade routes among early civilizations.

The ancient Sarzm settlement is located about 15 km west of Panjakent on the left bank of the Zarafshan River, and close to the border with Uzbekistan. Hence, it can also be visited by Samarkand. It is a vast settlement with the original uncovered area spanning 130 hectares. Archaeologists believe it is one of the oldest settlements in Central Asia, with the main occupation dating from the 4th millennium BCE to the late 3rd millennium BCE (the Eneolithic and Early Bronze Age). Its name comes from the Old Tajik word sarizamin, which means “the beginning of the land or where the land begins”.

The site’s strategic position makes it an early proto-urban center because it lay between nomadic groups and agrarian settlers. It later thrived in agriculture, mining, and trade along what would become the early trans-Eurasian trade routes.

Several open excavation sections at the Sarzam settlement allow visitors to examine these distinct layers of habitation. We recommend visiting the museum first, then seeing the site, as you will gain a lot of information about the different sites, their timelines, and the relics found there.

Historical Significance

The Ancient Settlement of Sarzam is an extraordinarily significant archaeological site that was once a thriving, well-developed center representing a crucial period in the history of Central Asia.

The site is an excellent example of the early rise of proto-urbanization in the region, where a slow transition from pure pastoralism to a more complex agrarian and industrial society took place. According to an estimate, at its peak, the settlement may have covered up to 90 hectares, connecting the pastoral nomads of the mountains with the agrarian peoples of the plains.

Sarazm’s strategic location made it a major inter-regional trade and cultural hub on the ancient trans-Eurasian routes (a proto-Silk Road). This vast network stretched from the Turkmenistan steppes and the Aral Sea in the northwest to the Iranian Plateau, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley (modern-day Pakistan/Ancient Northern India) in the south/southeast. Artifacts found, such as lapis lazuli from Badakhshan, demonstrate this long-distance trade.

It was one of the largest metallurgical centers in Central Asia during the Bronze Age. The inhabitants mined and processed metals such as copper, tin, lead, gold, and silver (the Zarafshan Valley is rich in these resources). Archaeological finds include bronze tools (axes, daggers, chisels) and decorative objects.

Archaeological Findings and Importance

The site was discovered in 1976, and shortly after, excavations began that uncovered fascinating history buried in layers from 3500–3000 BC until the site was abandoned. The site was gradually abandoned sometime between the middle and end of the 3rd millennium BCE, possibly due to a prolonged period of drought. It has 8-10 open excavation areas where you will be able to see the ruins, well-marked with various timelines and what was found there.

Main Highlights of the Site:

- Excavation IX is located on the southeastern side of the Sarazm settlement, where archaeological work began in 1988. The site contains three main cultural horizons. Horizon 1 revealed two different types of construction complexes, likely residential. Horizon 2 uncovered wall remains and a two-storey pottery kiln. Horizon 3 featured two specially constructed suite-room buildings that shared the same architectural layout. Both structures had a central rectangular hall with square fire altars, indicating ritual or ceremonial functions.

- Excavation III is located on the southeastern part of the Sarazm settlement, on a mound rising about 3 meters above the surrounding area. The excavation revealed the foundations of a large, uniquely designed building covering roughly 410 square meters. Its scale and architectural layout suggest that it served an important public function within the ancient settlement.

- Excavation V, located in the central part of the Sarazm settlement, covers 668 square meters and contains mud-brick structures from four occupation horizons. The findings show a variety of architectural forms, including circular buildings and corridor-like structures, as well as larger, more complex buildings, including one with a rectangular plan and architectural features such as windows and stairs. Another structure displayed an exterior wall reinforcement system using pilasters and counter-forts, indicating advanced construction techniques. These monumental buildings, including a palace complex, a communal granary, and religious structures with circular altars, are believed to be the oldest Pre-Zoroastrian monument of the fire cult in the region.

- Excavation IV is situated in the southwestern part of the site. The remains of a building were researched, and a necropolis was found surrounding a stone fence with a diameter of about 15 m and a height of 0.7 to 0.75 m. Above the necropolis, in the cultural layer, a house with fire altars was discovered. This site also contained the burial of a wealthy woman, known as the “Princess of Sarazm,” who was interred with a veil and clothing heavily adorned with thousands of turquoise and lapis lazuli beads, as well as seashell bracelets. Her elaborate burial indicates significant wealth and social standing approximately 5,500 years ago. Her skeleton and associated artifacts are preserved in the National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan, Dushanbe.

- At Excavation VIII, four entrances with brick thresholds, each 75–80 cm wide, were identified along the perimeter of the structure. In the southwestern corner, a large refuse pit was uncovered, containing numerous bones, ceramics, stone tools, and flint plates. The layout, the evidence of religious activity among the Sarazm population, and the presence of hearths (fire altars) indicate that this complex of rooms formed a cohesive, intentionally planned architectural ensemble.

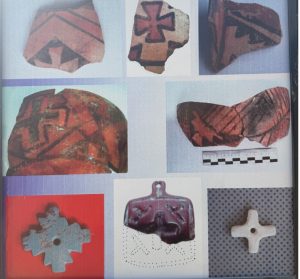

Various Discoveries Related to the Image of the Cross in the Pre-Christian Era. Image Courtesy: The Site Museum

- Various findings with an image of a cross at Sarzam settlement.