Navigate to Sections

A Guide to Navigating Chile’s Travel Requirement for Rapa Nui

Essential Preparations Before Visiting Rapa Nui

Traveling to Rapa Nui requires attentive planning, more than booking flights, accommodations and transportation, etc. The Government of Chile has strict requirements to travel to Rapa Nui to protect its fragile environment. You must fulfill these requirements before you can board the plan to Rapa Nui, regardless of if you are a Chilean citizen or a foreigner.

Here are the steps:

- Book your flights to Easter Island/Rapa Nui: The airport code is IPC. LATAM Airline is the only airline that fly to Easter Island/Rapa Nui, and only from Santiago (SCL). You must book a return ticket as a tourist. You will be asked to show a return ticket.

- Book your accommodation: You can stay for a maximum of 30 days on Easter Island. Only reserve a SERNATUR (National Tourism Service) authorized accommodation, may it be a hotel, bed and breakfast or a short-term rental such as Airbnb or VRBO. Ask your accommodation provider if they are registered with SERNATUR. You can search for SERNATUR approved accommodations on their (Spanish only) Website. Note that Rapa Nui is in the Valparaiso Region. Be prepared to show your reservation at the airport.

- Fill in online Rapa Nui single entry form, called Formulario Único de Ingreso a Isla de Pascua (FUI): Do this 3-4 days before your departure. This is a mandatory step, you won’t be able to board your flight without it, don’t do it the day of your flight or at the airport. Please make sure to book your flights and accommodation, you will need to provide the information when filling out the form. You will get email confirmation and will need to show it at the airport.

- Arrive early for your Easter Island flight: It is like going on an international flight. After you check-in at the LATAM counter and get your boarding pass etc., don’t go to the domestic security checkpoint. We made this mistake; the airline counter staff did not tell us where to go. There is a special departure area on domestic terminal’s second floor for Rapa Nui where Chile Policia Nacionalprocesses the FUI mentioned above, very similar to passport control. The Chile Policia Nacional will give you a paper permit that you will need to give to the police when boarding the plane; you won’t be able to board the plane without it.

- Food Import Regulations: Chilean citizens (not foreigners) are permitted to bring only tightly packaged food items to Rapa Nui, both upon entry and departure, excluding fruits, seeds, grains, vegetables, or unprocessed animal products. Fresh fruits and vegetables are strictly prohibited and must be disposed of before reaching customs at the airport or declared and surrendered. Additionally, honey products are not permitted to be brought to Rapa Nui. We had to discard some amazing mangoes that we purchased on the island and intended to bring with us to enjoy at the airport while waiting.

Visiting Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, can indeed be a transformative experience, particularly when viewed through a historical lens. Exploring the island’s history reveals chilling details. Once a place of prosperity and sustainable growth, marked by the construction of Moai statues and a rich spiritual tradition, Rapa Nui later descended into turmoil. The abandonment of ancestral practices and the toppling of sacred idols led to a vacuum of order, which was eventually filled by a new cult. However, this narrative is far from complete—it encompasses bloodshed, exploitation, depopulation, and even cannibalism. It’s sobering to realize that this tiny island and its inhabitants navigated significant challenges without external assistance.

Evidences point to periods of extreme social unrest and a struggle for survival, where desperation led to the normalization of violence and the consumption of human flesh. Early Western accounts describe a lack of women and children on the island, with human bones scattered across the landscape—a testament to the harsh realities faced by the island’s inhabitants. Resources were scarce, and the imperative of survival often meant that even the basic burial rituals were neglected. Rapa Nui’s history serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of human civilization and the lengths to which people will go in the pursuit of survival.

In this blog, we will explore how ecological change catalyzed societal transformation, including the evolution from intriguing practices such as Moai, the concept of mana, spiritual power used for protection, to the emergence of the Birdman cult, where the deity is represented by a powerful man who can procure the Sooty Tern bird’s first egg.

Rapa Nui’s Settlement and Survival

Easter Island, comparable in size to Washington, DC, can be explored on foot within a day. Its formation is attributed to lava flows from three major volcanic eruptions and various minor ones over time. Each corner of this triangular landmass boasts an extinct volcano, collectively shaping its 63 square miles (163 square km) of landscape amidst the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

According to the initial estimates, the first inhabitants came around 400-800 AD, but radiocarbon dating in 2007 suggests a more accurate timeline closer to 1100-1200 AD. Like settlers on the other Polynesian islands, the migrants to Rapa Nui were driven to explore new lands, probably due to conflicts or resource shortages in their homeland. According to oral traditions and genealogical analysis, these settlers came from Tonga or nearby islands, embarking on catamaran-like canoes. They brought essential supplies such as seeds and animals, including chickens, pigs, and rats. Unfortunately, the pigs did not survive the voyage, leaving the settlers with only chickens and some plants to sustain themselves upon their arrival on Rapa Nui.

Resource Scarcity and Adaptation

Easter Island is different from other Polynesian islands as it had no freshwater streams. The settlers had to depend on freshwater reservoirs within volcanic craters or collect rainwater for their daily needs, including agriculture. However, the crops they brought with them, such as bananas and taro, required a lot of water for cultivation.

They also had limited protein sources, with only chickens they domesticated and some fish to rely on. Unlike Hawaii, Easter Island had few coral reefs, leading to a shortage of fishing opportunities. Additionally, the absence of land mammals meant they did not have the bones necessary for crafting fishhooks; instead, they started using human bones to create fishhooks as per the evidence found.

Despite its limited resources, Easter Island was rich in one particular resource: giant palm trees. With 16 million palm trees, the majority of which grew up to 100 feet, the island’s inhabitants relied heavily on them for various purposes, including food, shelter, building canoes, and tools, making them vital resources to sustain life on the island.

The people of Rapa Nui Island underwent a profound spiritual crisis when they turned away from their traditional Moai statues, which had long been central to their cultural and religious identity. This abandonment resulted in social unrest and a sense of disorder within the community, which they filled with creating the Birdman competition, which provided a new framework for social organization and cohesion.

The Rise of the Moai Sculptures

As migrants from Polynesia, the Rapanui people brought with them their spiritual beliefs, which included the worship of the Make-Make (Tane) god, the belief in the existence of spirits, and ideas about the afterlife. These beliefs played an essential role in shaping their cultural and religious practices, influencing their worldview and societal norms. However, as time passed, their beliefs and traditions evolved. One of the most prominent features of Rapanui culture is the construction of Moai, massive sculptures that served as a tribute to their ancestors and protected the community. Although this practice is a common spiritual concept in many societies worldwide, the central themes of Rapanui culture remain to honor the past and to safeguard the land.

Easter Island’s volcanic rock provided a unique medium to carve into monumental statues, unlike other Polynesian islands. According to an estimate, the Moai statues were created by Polynesians on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) between the 12th and 17th centuries. These statues were made to hold their deceased ancestors’ spirits, so they convey their supernatural power, or mana, to their descendants. The techniques used to carve the volcanic rock are still debated. However, some speculate that the Polynesians learned from indigenous people on Rapa Nui due to their limited experience with volcanic landscapes. This points to whether the early Polynesians ever came across South Americans who knew the use of such volcanic rocks. Regardless of their origins, the Moai statues are impressive symbols of Rapanui culture and craftsmanship, showcasing both spiritual reverence and artistic mastery.

During times of abundance, art flourished, and people could focus on satisfying their spiritual needs. The creation of the massive Moai statues on Easter Island is a testament to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which suggests that fulfilling basic physiological needs is crucial to human motivation and behavior. Once these needs are met, individuals are more likely to engage in higher-level activities like creativity and artistic expression. Building the Moai statues required significant time, effort, and resources, which would have been challenging if the population had already struggled to meet their basic survival needs.

The Tragic Demise of the Giant Palm Trees

Unfortunately, this hustle and bustle on Easter Island was short-lived, and the disappearance of the giant palm trees was a tragic consequence of human activity. Many people believed the trees were cut down to help transport the Moai statues, but recent research suggests that the true culprit was the proliferation of Polynesian rats. The rats, introduced by early settlers, consumed the palm nuts, preventing the trees from regenerating. The absence of natural predators allowed the Polynesian rat population to thrive unchecked, which worsened the environmental devastation in addition to the deforestation habits of the inhabitants. That ultimately led to the extinction of the palm trees.

The island was once lush with flora, particularly the towering palm trees that provided essential resources such as sugary palm and nutrition-rich nuts. The disappearance of these trees had cascading effects on the smaller vegetation that had coexisted with them for millions of years. This sudden ecosystem change devastated other plant species and birds that relied on them for survival.

Cooking pots excavated from the caves revealed an increasing abundance of small bones from seabirds. Over time, all of the original landbird species became extinct, and the twenty-five different seabird species that once nested there were wiped out due to the extinction of towering palm trees.

Notably, the absence of palm trees removed a natural barrier that had sustained the island for millions of years by protecting it against strong winds and salt spray on the crops. This loss of vegetation not only had ecological consequences but also impacted the cultural and societal dynamics of the Rapanui people. A struggle for resources ensued, and the principle of survival of the fittest came into play. The extreme social conflict and uprise led the Rapanui people to seek shelter underground, within the lava caves. They, however, tried to make the island sustainable by growing crops inside the caves to protect them from wind and salt spray.

The Fall of the Moais: A Glimpse into Rapa Nui’s New Dark Chapter

Thin Moai Kavakava from Easter Island Found at Museo Etnográfico Juan B. Ambrosetti, Buenos Aires

More than such efforts was needed to feed thousands of people. Famine spread rapidly, and new statues began to depict the horrors of hunger and desperation with the depiction of bellies protruding, ribcages extended and faces twisted in pain and hunger, unlike calm Moais of the past. They abandoned and toppled their ancestors’ traditional Moais. A query (workshop) where Rapanuis used to carve Moais still holds many incomplete Moais. Some Moai statues were partially buried in soil, while others remained intact on the crater wall where they were carved. The largest Moai, as can be sees in the image below, was ready to be transported. But both the means and will were gone. The inhabitants’ belief in their ancestors’ tradition was lost, leading to a vacuum and spiritual crisis that resulted in anarchy and chaos.

Abandoned Moai (the Largest One) at the Quarry

Trapped without the means to escape the social unrest, they resorted to fighting amongst themselves with no wood or trees to build canoes and flee.

Ana Kai Tangata “Cave of the Cannibals”

Researchers are intrigued to find that despite the temperate weather above ground, they opted for living underground inside the lava caves. Archaeologists discovered chilling evidence of human activity inside these caves, including walls, fireplaces, paintings and human bones.

One cave, named Ana Kai Tangata, illustrates this dark chapter in Rapa Nui’s history. “Ana” means cave, while “Tangata” means man. The meaning of “Kai” is ambiguous, possibly referring to a place where “men eat” or “eat man cave” — Cave of the Cannibals. With no other food sources available, cannibalism became the grim reality for those struggling to survive.

Instances of cannibalism have been documented in various traditions. Some individuals living underground broke this taboo and began killing and consuming other humans.

Building walls at the cave entrances was a significant undertaking designed to provide security and concealment. These walls were strategically constructed to let inhabitants enter the lava tubes discreetly. Across the island, various escape routes and camouflaged entrances were established. Inside the caves, artifacts such as basalt weapons, including razor-sharp spearheads made of black, shiny volcanic rock, were found. Interestingly, there was no evidence of widespread, large-scale warfare or conflicts. These weapons were likely used for combat, suggesting a shift from organized society to chaos, especially following the cessation of Moai construction. As competition for limited resources intensified, tensions escalated among the human population, leading to the emergence of different clans based on immediate blood relations and access to resources.

According to some oral traditions, battles among clans ensued where the defeated fled to caverns, only to be captured and consumed by the victors. Well, who were those victors? This was the time when a new cult under the priest’s guidance emerged, the Birdman cult, and the victors were the champions who won the Birdman race. To address the issue of who would hold the prime spot for sustenance, a democratic solution emerged in the form of the birdman race.

What was that race? Competitors, always men, known as hopu, descended Orongo’s steep cliff and used bundles of reeds to float and swim to the nearby Motu Nui islet, approximately two kilometers away from mainland Rapa Nui. They would run across treacherous waters and escape sharks to reach Motu Nui, an islet, where they awaited the arrival of the manutara birds (Sooty tern). They carried the precious manutara egg wrapped in a piece of cloth tied around their forehead to keep their hands free while swimming.

The newly appointed Birdman selected some people for the sacrifice, and there is a hint that cannibalism was also performed during the feasting rituals. The people appointed by the new Birdman for sacrifice often became the cause of further wars.

Cannibal feasts may have been held during the time of the Birdman cult, with bones from both animals and humans found in these caves. The presence of a carved ceremonial skull further underscores the solemnity and significance of this site. Additionally, the cave lies near the start of trails leading to Rano Kau and Orongo, adding to its historical and cultural importance.

Another chilling aspect is the Polynesians’ fascination with Sooty Terns, which is understandable, given their unique characteristics, such as their ability to soar over the ocean without an oily film on their wings. Unlike other seabirds, they employ clever tactics rather than swimming to catch prey. They attack other birds, causing them to drop their prey. Swiftly, the sooty tern dives to catch the falling fish before it touches the water, ensuring a successful hunt. The resilience of the sooty birds in such an environment likely inspired admiration and reverence among the islanders, further cementing their importance in Polynesian culture. These migratory birds were revered as messengers embodying divinity, soul, omen, and food resources, thus becoming totems for the people. This reverence played a pivotal role in the origin of the Birdman cult.

The Emergence of the Birdman Cult

During that perilous time, they abandoned Moai and toppled the ones erected by their ancestors. The spiritual traditions associated with Moai transformed into a crude birdman race cult. This shift involved manipulating power dynamics, exploiting followers, and imposing rigid ideas. A priest replaced the king as the owner of a new tradition, typical of a cultish scenario. (It is imperative to mention that king was not allowed to observe the race. It was just the priest who was the caretaker).

Orongo, a small village, was the center of the Birdsman cult between the 18th and mid-19th centuries. Priests and clan chiefs gathered to observe the tangata manu (Birdman) ritual. Visitors can observe the surviving (restored) three stone houses facing the Motu Nui and Motu Ilti (two tiny islands close to Rapa Nui). These houses were built explicitly for the priest, who continuously prayed and chanted for the contestants’ success.

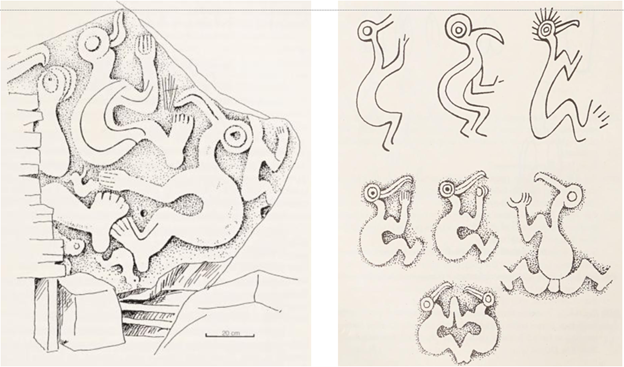

An Image of the Petroglyphs Panel Inside the Cave and Evolution of the Birdman Motif- Courtesy: Lee, Georgia. Rock Art of Easter Island: Symbols of Power, Prayers to the Gods. 1926. Page 28 and 36

After every successful expedition, a petroglyph was carved on the rock inside one of the caves to make this cult more ceremonial. There are 185 motifs associated with this ritual continued. These petroglyphs are buried under the tall grass. Petroglyphs are diverse in size, from one motif to twelve-meter panels of petroglyphs that were neglected until 1981 when the work on understanding these petroglyphs was started.

Researchers found the birdman motif carved inside the caves and on rocks scattered all over Rapa Nui. The motif changed over time from simplified to more complex. It was not just the physical appearance of the birdman motif that became complex but the creators thought process as well. The later staged motifs represent something related to fertility by depicting a half man and half bird, probably during extreme population decline and yearning for an increase in population. Still, a lot remains unknown about this short-lived, remotest community that created them. Unfortunately, this rock art has been vanishing because of withering, erosion, and vandalism.

Encounters with Westerners: Adding to Rapa Nui’s Suffering

The misery of the Rapanuis did not end there; the arrival of Dutch, Spanish, and other European immigrants brought disease and Christianity to the island, which had devastating consequences for the indigenous population. As a result, many of the stories and traditions passed down by the Rapanuis were lost. According to an estimate, there were about 10,000 Rapanuis at its peak, which was later reduced to 3000 when the first Dutch arrived, probably due to the Rapa Nui not being able to sustain that many populations. According to early European accounts, there were mostly men; they did not see children and women, and human bones scattered all over the island. That points to extreme social upheaval and misery that people did not even bury their deceased.

In the early 1900s, the indigenous population dwindled to only 101 individuals. Today, the indigenous community is predominantly Christian and of mixed race. No single family carries 100% indigenous DNA, but they still hold on to their ancient traditions. This is partly because they receive benefits in exchange for the sacrifices they make and partly as a form of compensation.

Today, the island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its ancient mysteries and enduring legacy draw visitors from around the world.

The island’s history illustrates the inevitability of change and the need for resilience in the face of evolving circumstances. As the world grapples with environmental challenges and geopolitical transformations, the lessons from Rapa Nui resonate: nothing remains permanent, and change is inevitable.

Sources:

- Smith, John. “The Changing Landscape of Easter Island.” Pacific Journal of Archaeology, vol. 12, no. 3, 2023, pp. 45-60. Gale Academic OneFile

- Stevenson, Christopher M., et al. “Architecturally Modified Caves on Rapa Nui: Post-European Contact Ritual Spaces?” Rapa Nui Journal, vol. 32, no. 1-2, May-Oct. 2019, pp. 1+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A655812726/AONE?u=spl_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=f727f1d4. Accessed 16 Apr. 2024.

- Jones, David T. “Easter Island: what to learn from the Puzzles?” American Diplomacy, 6 Nov. 2007, p. NA. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A172252138/AONE?u=spl_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=0078e701. Accessed 16 Apr. 2024.

- Bahn, Paul G., and John Flenley. Easter Island, Earth Island. Thames and Hudson, 1992. Google Books

- Lee, Georgia. The Rock Art of Easter Island: Symbols of Power, Prayers to the Gods. University of California Press, 1992. Archive.org, archive.org/details/rockartofeasteri0000leeg/page/n5/mode/2up.

- Pelta, Kathy. Rediscovering Easter Island: How History Is Invented. Learner Publications Company, 2001.

- Macri, Martha J., and Jo Anne Van Tilburg. “From Ethnographical Subjects to Archaeological Objects: Pierre Loti on Easter Island (Rapa Nui).” Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, vol. 24, no. 1, 2014, archaeologybulletin.org/article/view/bha.2410.

- “Orongo.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Mar. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orongo.

Video